Handmade in India is a centuries-old tradition that needs to be cherished, preserved, and promoted. It’s a form of creation that deserves to be nurtured, celebrated, and spread. This is what we try to do in our posts on #HandmadeinIndia, all of which can be read, seen, and shared here.

Today in Handmade in India, we take a trip into the heart of Gujarat to take a closer look at the handiwork of three communities that have handmade for India for centuries. Welcome to their world.

1. The Chitaras of Ahmedabad

Welcome to the Vasna area of Ahmedabad. We’re here, among a few artisans that produce hand-painted ritualistic cloth, called Mata Ni Pachedi and Mata Ni Chadarvo, to meet Sanjay Chitara.

A family of master artisans, Sanjay, his mother, Manjuben Chitara, and brother, Vasant, have all won national awards for ‘kalamkari’, the art of drawing with a handheld pen.

On the fine art of ritualistic cloth painting, Sanjay says, “My father, Manubhai, and his family used to prepare the Mata Ni Pachedi and Mata Ni Chadarvo cloth for rituals in a distinctive painting style passed on through generations of the Vaghari community, using colours extracted from vegetables, flowers, herbs and other natural sources. The Mata Ni Pachedi and Mata Ni Chadarvo cloths are offered to the mother goddesses especially during Navratri. They become scaffoldings for temporary shrines created during the festivals and then are immersed in the rivers.”

Sanjay Chitara adding colours to one of his Mata Ni Pachedi creations

At home, Manubhai, his wife Manjuben, his sons Sanjay and Vasant, their respective wives Kailash and Pinky, all work together on these paintings — preparing the fabric, making the dyes, drawing, painting and fixing.

To prepare the fabric, the dyes are made from natural materials – madder and alum for red, henna for orange, pomegranate and mango extracts for yellow, indigo for blue, iron and molasses for black and so on.Myrobalan (a tropical tree with nuts) extract, herbs, tamarind seeds, and castor oil are used in dyeing process.

“After treatment with Myrobalan and applying alum for the red, the fabric is immersed in the River Sabarmati, in Ahmedabad, after which the other colours are applied,” says Vasant Chitara.

Mata Ni Pachedi by Sanjay Chitara

While bold borders are characteristic of Mata Ni Pachedi art, the family makes drawings of Amba enshrined in a temple, with a shikhara (tower) which has a dome or chattri next to it. Another shrine could be a hilltop temple, a third could have the goddess on a colourful background with rich brocade borders. Black and reddish maroon are dominant colours in the traditional Pachedi, though over the years the artisans have begun to add more colours.

Their paintings are exquisitely detailed and make perfect art pieces. “The result of our expertise and artistry was that I was one of the master craftspersons and weavers selected from all over the country for National Awards in 2000. While my brother Vasant won the National Award in 2001 and my mother Manjuben, in 2004.”

Interesting tidbits about Mata Ni Pachedi

- Mata Ni Pachedi literally translates to “behind the mother goddess” in Gujarati. When the nomadic Vaghari community from Gujarat were barred from entering temples, they made their own temple in the form of a cloth with an intricate painting of the Mother Goddess. This is believed to be the origin of the sacred art called Mata Ni Pachedi.

- This art form is believed to be a 300-year-old tradition and has only a few dedicated practitioners remaining.

- The art is very similar to Kalamkari art practiced in South India which involves the use of pens (kalam) fashioned out of bamboo sticks.

2. The Prajapati Block Makers of Pethapur

Pethapur is one of India’s leading centres for the making of woodblocks used for textile printing.

According to Govindlal Prajapati, one of the craftsmen from Pethapur, “Pethapur has been a centre for carpentry for centuries. The carpenters realised the potential for making wood blocks for printing and since then it has been the main source for wooden blocks. I have been making blocks from the age of 12 working under a master craftsman, the late Hiralal Gangaram Gajjar. Hiralal’s descendant, Ganshyamlal Popatlal Gajjar, is a good craftsman and runs a block making unit.” Maneklal Gajjar has won a National Award for his wooden blocks.

Master craftsmen Govindlal Prajapati (Picture Courtesy: Priyanka Rangthale)

“There were about 300 craftsmen during my youth but with the growth of modern occupation opportunities many families gave up this handicraft. Today, there are just 12 craftsmen in Pethapur who follow this tradition,” says Govindlal.

Govindlal who is currently in his mid-60s, recalls that Pethapur in his childhood was also a centre for block printing textiles, much of which went to Java and Sumatra. Govindlal today runs his workshop with his son, Satish Prajapati.

“Apart from my son, I also encouraged my nephews to learn the art of carving wooden blocks. My nephew, Mukesh Prajapati, is one of the country’s finest wood block makers. He runs his workshop with his sons, Avdesh and Pragnesh, and his nephew, Bhavesh – all three of whom are good carvers.” he says.

The surface of the teakwood block to be used for printing is planed and smoothed to be completely flat. The drawing is transferred by means of sticking a paper on it.

“For geometric patterns we use graph paper while for symmetrical, floral and other designs we do it on regular paper. The pattern is then carved out on the block with holes created to let out air at the time of pressing the fabric on the fabric. When ready, the pattern on the woodblock appears like a high-relief carving.

Wood Block Carving (Picture Courtesy: Priyanka Rangthale)

“Pethapur is a national hub for woodblocks used for textile printing. The four or five workshops in the village supply carved wooden blocks across the country from wherever the art of textile printing using hand-held blocks is still practiced. In Gujarat, we supply blocks to Kutch, Jetpur, Ahmedabad and other centres of the state for woodblock printing, discharge prints, batik, etc,” says Govindlal.

Interesting tidbit about Block Making

Printers of different areas use different motifs or techniques and these block makers are experts in making all kinds of blocks.

- Ajrakh prints are known for their geometric and star patterned motifs

- The Sanganeri prints of Rajasthan carry simple, abstract or floral motifs.

- The Bagh prints of Madhya Pradesh also have abstract florals, although more intricate than the Sanganeri ones.

- The most intricate were the Saudagari prints, from which the block making art is believed to have started in Pethapur. These prints are extremely difficult even to be hand-drawn, but the craftsmen of Pethapur are able to make perfect wood blocks. However, the Saudagari prints are not done anymore.

3. The Salvi Weavers of Patan

The Patola is one of the finest of Double Ikats. Considered the premiere form of Ikat, Double Ikat requires the most skill for precise patterns to be woven and is so complex and time consuming to create that they are rarely woven, except in a few places in India, Japan and Indonesia.

Double Ikat is a technique where both the warp and weft threads are resist-dyed to create the patterns of textiles before they are set on the loom. The Patola textiles, made using the Double Ikat technique are extraordinary pieces of art.

“Today, only three families in Patan and one in Vadodara make the Double Ikat Patola. We all belong to the extended Salvi family, which has separated to form different family workshops. The four families are those of Kantilal Lalubhai Salvi, Sevantilal Lerchand Salvi and Kantilal Lerchand Salvi in Patan, and Mafatlal Dayalal Salvi who moved to Vadodara,” explains Satishchandra Salvi.

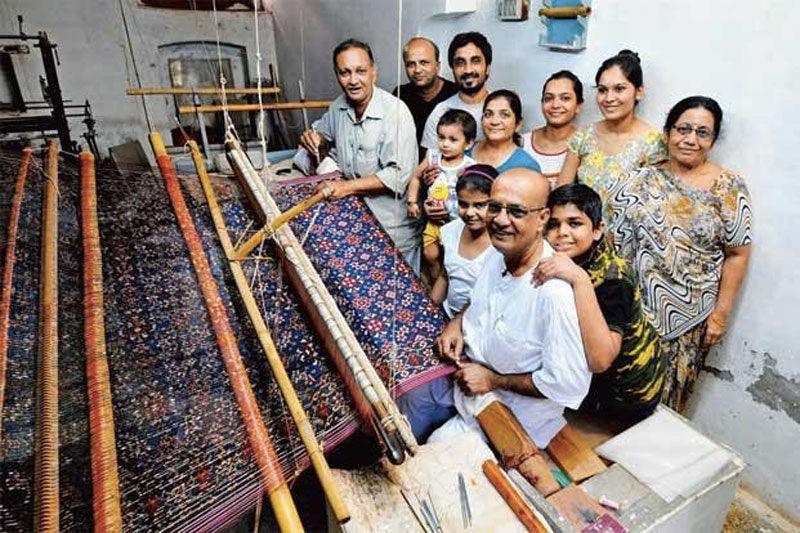

The Salvi family at their home in Salviwaddo, Patolawala street, in Patan, Gujarat

In the last two decades, many excellent weavers like Chhotalal Salvi, Vinayak Salvi, Bharat Salvi, and Kantilal Salvi, to name a few, have won national awards. Satishchandra Salvi, who was selected for the Sant Kabir Award 2009 says that the entire family is involved in the complex process of weaving the Patola.

“At my workshop, my brother Paresh and I work with the help of our sisters and wives, to go through all the processes from resist-dyeing of the threads to the completion of the weaving. Similarly, in Vadodara, Mafatlal, his son Kanubhai and his two daughters, Neepa and Hetal, are carrying on this tradition.”

Most of the silk is brought from Bangalore and some, imported. The designs are usually drawn on graph paper and then copied on to the yarn. The number of threads required is calculated according to the design. And this must remain constant till the entire weaving of the sari is done, as the measurements are very minute.

The artisans have to carefully monitor the tension of the warp and weft threads during the weaving process. The completed sari has the same pattern on both sides.

“Since vegetable dyes are used, we can assure that the fabric of the Patola may tear but the colour will never fade for centuries,” says Satishchandra Salvi proudly.

A finished Patola sari

The process of tie-dyeing the threads can take up to 75 days. The dyed threads are then strung on the loom in a sequence that makes the design visible. The weft threads are wound on to bobbins and fed through the bamboo shuttle. Working on a hand-operated loom that is slightly inclined to make it easier to move the shuttle, three to five people work a sari, which can take anything from four to six months to finish.

Interesting tidbits about Patola saris

- Believed to usher in luck and prosperity, a Patola sari is passed on as an heirloom or worn during baby showers.

- Each sari can survive over a century without losing its colour or lustre.

- The square in the pattern represents security in all walks of life.

- The elephant, parrot, peacock and kalash (metal pot) are auspicious symbols.

And some more

The Salvis get their name from ‘Sal’ (Sanskrit for loom) and “Vi” (the rosewood sword used in a Patola loom).

Source: www.gujarattourism.com